Mitchell Robinson (right) had ankle surgery before last season and was limited to 17 games after he returned.

NEW YORK (AP) — New York Knicks coach Mike Brown will have to wait to show whether Josh Hart or Mitchell Robinson will start for him….

Mitchell Robinson (right) had ankle surgery before last season and was limited to 17 games after he returned.

NEW YORK (AP) — New York Knicks coach Mike Brown will have to wait to show whether Josh Hart or Mitchell Robinson will start for him….

This request seems a bit unusual, so we need to confirm that you’re human. Please press and hold the button until it turns completely green. Thank you for your cooperation!

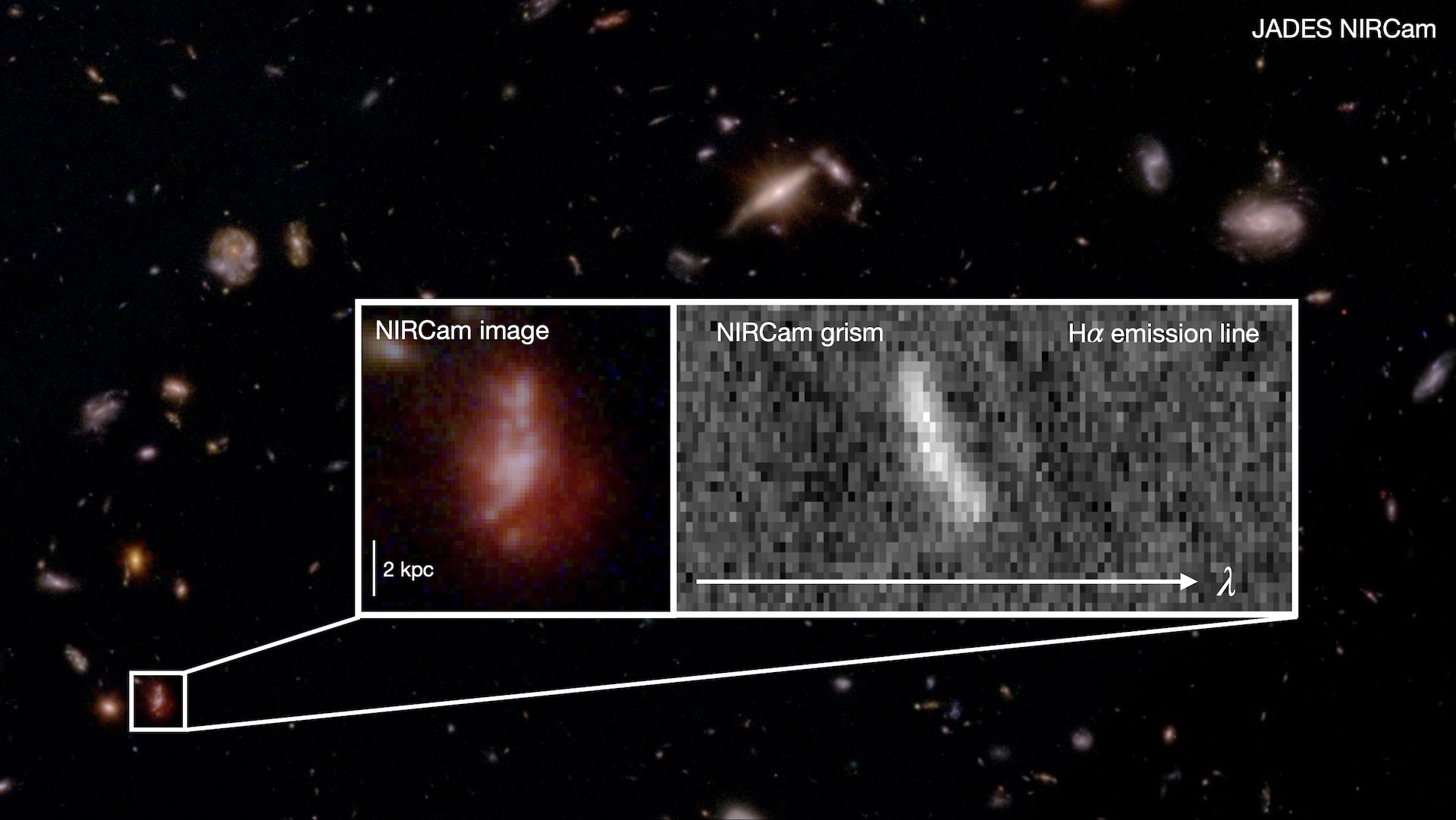

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have captured the most detailed look yet at how galaxies formed just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang – and found they were far more chaotic and messy than those we…

Papillary muscle scarring (papSCAR) as detected by dark blood delayed-enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) was present in 1 in 3 patients with

No major bank has yet committed to stop funding new oil and gas fields or coal capacity, research has found.

Most banks that have recently updated their climate policies have weakened them, according to the research by the TPI Global Climate Transition Centre (TPI) at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

The centre analysed 36 of the largest banks by market capitalisation and total assets, and found “banks are still at an early stage of their transition with decarbonisation targets that cover a limited set of sectors and business activities.”

The researchers evaluated banks’ climate policies using 77 sub-indicators grouped into 10 areas, called the net zero banking assessment framework (NZBAF).

They found 95% of the scores remained unchanged year on year, and those banks that had shifted had weakened their policies. On average, banks score on only 18% of the 77 sub-indicators and the best-performing bank scores on about one-third of the sub-indicators.

The report said banks have “weakened their disclosures in areas such as net zero commitments, financing conditions for high-emission sectors and fossil fuel policies”. Some banks either fully withdrew or weakened their net zero commitments, substituting firm language such as “commitment” or “target” with less precise wording such as “ambition” or “aspiration”.

Algirdas Brochard, banking project lead at TPI, said: “Given banks’ central role in the economy and their far-reaching influence on climate, their slow progress on the climate transition coupled with the recent dissolution of the Net Zero Banking Alliance suggest that the objectives of the Paris agreement are slipping further out of reach.”

after newsletter promotion

As well as failing to stop funding fossil fuel projects, many banks are also not funding climate solutions and the green transition. Of the 36 banks TPI assessed, 17 have financing targets for climate solutions, but the activities eligible for this financing vary from bank to bank.

Another recent study found the world’s big banks have handed nearly $7tn (£5.6tn) in funding to the fossil fuel industry since the Paris agreement to limit carbon emissions.

This year, the Net Zero Banking Alliance shut down completely after leading banks quit it following the election of the US president, Donald Trump. It had encouraged members to cut the carbon footprint of their investments and help drive the transition to net zero emissions by 2050.

Vietnam’s economic rise is causing ripples around Asia, especially in Thailand. Any mention of the “V word” in Bangkok causes hand-wringing and furrowed brows among the city’s business executives. Vietnam is on track to overtake Thailand by the end of the decade to become Southeast Asia’s second-largest economy. Last week, Hanoi signed a new deal with Apple to expand production of smart-home devices in Vietnam – the latest in a series of big-money technology-sector deals.

Meanwhile, many Chinese tourists have been holidaying in Hạ Long Bay, Da Nang and Phú Quốc this year, rather than Bangkok, Chiang Mai and Phuket. This trend is likely to be temporary; besides, losing low-spending tour groups can be seen as a sign of Thailand’s increasing maturity as a destination. Even so, Bangkok’s business community needs its government to come up with a big idea to kick-start a slowing economy, attract new investment and deliver a much-needed injection of confidence.

Thailand’s prime minister, Anutin Charnvirakul, recently spoke about the “nightmare” of Vietnam surpassing his country. Though he deserves credit for addressing the elephant in Bangkok’s boardrooms, his administration is short on flagship projects. Somewhat surprisingly, it backed a controversial scheme to build a Panama/Suez-style canal through the country’s Kra Isthmus. This centuries-old idea, which has evolved from being about an actual canal into a proposal to construct a so-called land bridge, is probably a placeholder until strategists and policy wonks can come up with something better.

To fully understand the depths of Thai leaders’ despair requires some historical context. The country has long been one of the region’s top dogs: decades of Cold War-era investment and infrastructure from the US military arrived at a time when neighbours Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam struggled with various conflicts. Thailand’s good fortune – or clever diplomacy – created a comfortable consumer class and an era of complacency. Any early warning signals that did go off this century were drowned out by an influx of Chinese money. Fifty years after the Vietnam War ended, Thailand has slipped behind in manufacturing and is becoming more and more reliant on tourism. Bangkok might host a Formula 1 race in 2028 – something that Hanoi failed to achieve amid a corruption crackdown – but there’s little to rev up interest outside of the Thai capital.

The previous Pheu Thai-led government staked its future and that of the country on legalising casinos. It botched the public-consultation process and ended up losing everything, including power, but I have been surprised in recent months by the level of support that the idea still has among business owners. No one is pro gambling per se – far from it. They just want to see their government acting and creating momentum. The casino idea elicited plenty of overseas interest; corporate lawyers and dealmakers were busy travelling to Macau, Singapore and the Philippines to do due diligence on behalf of major foreign financiers. However, because of the Thai government’s refusal to take a gamble, political flip-flopping and a revolving cast of prime ministers, those investors will be looking elsewhere.

Thailand’s next election could happen as soon as March and it’s likely to be fought on the economy. All of the leading parties will need to think hard and bring grand ideas to the table that can deliver real change to make the country richer and less indebted. Now is not the time to become bogged down in idealism. Elitist debates about democracy or constitutional reform might win fans abroad but usually meet heavy resistance at home. Instead, parties need to inspire hope and start talking up the country on the campaign trail. Thailand continues to enjoy incredible advantages and has a huge head start over its neighbours that might never be closed even when Vietnam’s economic output eventually surpasses it. A prosperous Vietnam is good for a rising region still troubled by conflict – and it doesn’t need to come at Thailand’s expense.

James Chambers is Monocle’s Asia editor. You can read his lesson in cross-border communication in Southeast Asia here. Visiting and need big plans for Bangkok yourself? Check out our City Guide.

A blind man said he is living in a “personal lockdown” after having to move…

Like cosmic toddlers, galaxies in the young universe were messy and had difficulty settling down, a new study shows.

Using the powerful James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), scientists peered at more than 250 galaxies in the early universe. The…

Although the euro area has a single currency and a common monetary policy, lending practices differ across euro area countries in several ways that shape the pass-through of monetary policy. In a recent paper (Vilerts et al. 2025), we study a less-explored difference: the maturity of the relevant overnight interest rate swap (OIS) at the time of issuance of new loans. We use data from AnaCredit, a comprehensive euro area-wide loan-level database, covering about seven million new loans issued by banks to non-financial corporations (NFCs) in 2022-23.

This timeframe encompasses the series of post-pandemic rate hikes.

Our preliminary analysis reveals that structural factors, such as loan type, firm size, or loan maturity, explain only a small portion of the lending rate differences across euro area countries. This suggests that other loan characteristics may play a more significant role.

In our study, we break the interest rate on individual loans down into a ‘relevant risk-free rate’ and a ‘premium’ – the residual compensating banks for risk. The relevant risk-free rate is that of the OIS. For fixed-rate loans the maturity of the relevant OIS is equal to the maturity of the loan, while for floating-rate loans it is the maturity corresponding to the loan’s reference rate at origination.

For example, the relevant risk-free rate for a five-year fixed-rate loan is the five-year OIS rate on the issuance date. In contrast, for a five-year floating-rate loan benchmarked against a three-month EURIBOR and adjusted every three months, the relevant risk-free rate would be the three-month OIS rate. The premium is then calculated as the difference between the lending rate and the relevant risk-free rate.

We find striking cross-country variation (Figure 1) in the maturity of the relevant risk-free rates: in countries such as Latvia and Ireland, maturities are very short – around six months on average. Meanwhile, in other countries, such as the Netherlands, Malta, and France, they often exceed five years on average.

Figure 1 Cross-country heterogeneity in the maturity of the relevant risk-free rate (years)

These structural differences mean that monetary policy transmits with varying strength and speed across the euro area, depending on which segment of the risk-free yield curve dominates local lending. Two key questions emerge. First, to what extent can the cross-country variation in the rise of average interest rates on new loans between early 2022 and late 2023 be explained by differences in the evolution of the risk-free rates used to price loans to non-financial corporations? And second, how does the maturity of the relevant risk-free rate affect the pass-through of monetary policy rate changes to interest rates on new loans?

To address the first question, we employ a time-difference approach to analysing changes in interest rate levels. In particular, we compare interest rates – as well as adjustments in the relevant risk-free rates and shifts in the premium – on loans issued in two periods bracketing the 2022-23 tightening cycle.

They are the first quarter of 2022, before the first hike in July 2022, and the fourth quarter of 2023, after the final hike in September 2023. We find that most of the rise in interest rates on new loans during the post-pandemic tightening was driven by increases in the relevant risk-free rate (Figure 2).

Figure 2 ‘Before and after’ analysis of lending rates

(conditional change between the first quarter of 2022 and the last quarter of 2023, percentage points)

Three key observations emerge from the analysis. First, the pass-through of changes in the relevant risk-free rates to changes in lending rates exhibits notable cross-country variation. Some 11 countries experienced an increase in relevant risk-free rates exceeding four percentage points, with Latvia and Estonia experiencing the highest increases at 4.37-4.41 percentage points. In contrast, the Netherlands and Malta saw risk-free rates rise by only 2.85 percentage points. Second, the distinction between fixed and floating-rate loans does not always provide a clear explanation for the observed patterns. For the relevant risk-free rates, the change was particularly pronounced in countries like Latvia and Ireland, where floating-rate loans with short fixation periods are more prevalent. Similarly, a strong contribution of relevant risk-free rates was observed in Italy, despite its higher reliance on fixed-rate loans, which tend to have shorter maturities. Third, a large increase in the relevant risk-free rates does not necessarily result in the largest increase in lending rates. In several countries, the rise in relevant risk-free rates was offset by a decline in the premium, which moderated the overall increase in lending rates.

We then turn our attention to loans issued near ECB Governing Council meetings and use a stacked time-difference regression (following Bredl 2024)

instead of a simple before-and-after comparison. Specifically, we examine how the pass-through of monetary policy rate changes varies across loans priced off different maturities of relevant risk-free rates, now using the full set of actual changes in the policy rate, instrumented by high-frequency surprises (Altavilla et al. 2019). As shown in Figure 3, the pass-through from monetary policy rates to lending rates strengthens as the maturity of the relevant risk-free rates shortens.

However, applying this approach to the components of interest rates shows that this mechanical pass-through is not the only factor at play, as we see adjustments in premia smoothing differences in pass-through across loan categories. We find that premia increased less for loans linked to shorter maturity risk-free rates, which partially offsets the differences in the aggregate pass-through to lending rates.

Figure 3 Stronger pass-through at shorter maturities

There are several possible explanations for this pattern. On the lender side, repricing of loans can at times outpace the pass-through to funding costs, improving net interest income, and creating scope to lower premia on new loans – especially for those priced off short-term reference rates. On the borrower side, tighter policy can alter the composition of lending and firms may substitute borrowing across maturities and rate types. Overall, the evidence points to systematic smoothing effects: premia adjustments dampen differences in loan rate changes. This suggests that the variation reflects pricing within banks rather than shifts in the banks doing the lending.

Our results point to several important implications for monetary policy. First, loan pricing design matters for monetary policy transmission. Markets where lending is tied to shorter maturities exhibit stronger and faster transmission. Second, loan premia also adjust independently of exogenous factors. When short-term rates move sharply, banks reprice loan premia over the relevant risk-free rate in ways that smooth differences across loans priced off different maturities. Recognising this interaction helps explain cross-country differences during tightening episodes and anticipate how the composition and pricing of new credit respond to policy.

Authors’ note: This column first appeared as a Research Bulletin of the European Central Bank. The authors gratefully acknowledge the comments from Alexander Popov and Zoë Sprokel. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the European Central Bank, the Eurosystem, or the International Monetary Fund.

Altavilla, C, L Brugnolini, R S Gürkaynak, R Motto and G Ragusa (2019), “Measuring euro area monetary policy”, Journal of Monetary Economics 108(C): 162-179.

Bredl, S (2024), “Regional loan market structure, bank lending rates and monetary transmission”, Working Paper.

Vilerts, K, S Anyfantaki, K Beņkovskis, S Bredl, M Giovannini, F M Horky, V Kunzmann, T Lalinsky, A Lampousis, E Lukmanova, F Petroulakis and K Zutis (2025), “Details Matter: Loan Pricing and Transmission of Monetary Policy in the Euro Area”, ECB Working Paper 3078.

Have you ever looked down at your favorite sweaters and just thought “yuck.” I recently pulled my sweaters out of storage as the weather has been cooling down, and some of them had definitely seen better days.

Luckily, I’ve found a hack…